What single recent event in a woman’s life is most strongly associated with her subsequent suicide attempt? A sexual assault.

In a large, nationally representive study in France, for instance, the odds that a woman would attempt suicide were 17 times higher if she had experienced a sexual assault in the last year than if she had not, the most potent risk factor among those examined. In fact, although sexual assault is associated with many poor mental health outcomes, such as depression, anxiety, and PTSD, it is most powerfully associated with suicidality.

Sexual assault often causes suicidal behavior, my graduate student Kristen Syme and I argue, precisely because women who report sexual assault are frequently not believed. An assault victim’s suicidal behavior is a last-ditch effort to convince others that she is telling the truth.

Our hypothesis is based on costly signaling theory: When individuals have conflicts of interest and incentives to lie, costly signals can still be trusted.

To illustrate: Imagine that Molly is sexually assaulted by her mother’s boyfriend, Mike, but there are no witnesses. Molly tells her mother about the assault, but her mother doesn’t believe her. Molly blamed Mike for her parents’ divorce. The mother suspects Molly is falsely accusing Mike of sexual assault to force her to break up with him and spend more time with Molly.

Molly, on the other hand, knows that Mike will probably attack her again. She is already traumatized, and if she gets pregnant by Mike, her life will be ruined. If she can convince her mother that she is telling the truth, she hopes her mother will put her daughter’s welfare first, and break up with Mike.

Molly swallows a bottle of pills shortly before her mother gets home from work. Molly’s suicide attempt, we argue, is a costly signal to her mother that she is telling the truth.

The logic is as follows. For Molly, the cost of a suicide attempt is low: if her mother doesn’t get rid of Mike, Molly’s life is probably ruined anyway. Her future is dim, and she is indifferent between being raped again and dying.

But if Molly were lying, if she had not been attacked and did not face any risk of being attacked, then the cost of a suicide attempt would be high: Molly is a young healthy women who, yes, isn’t getting as much attention from her mother as she would like, but her future is bright. A suicide attempt is too costly for her.

The fact that Molly would only attempt suicide if she faced a real risk of future attack by Mike convinces her mother that she is telling the truth. Her mother breaks up with Mike.

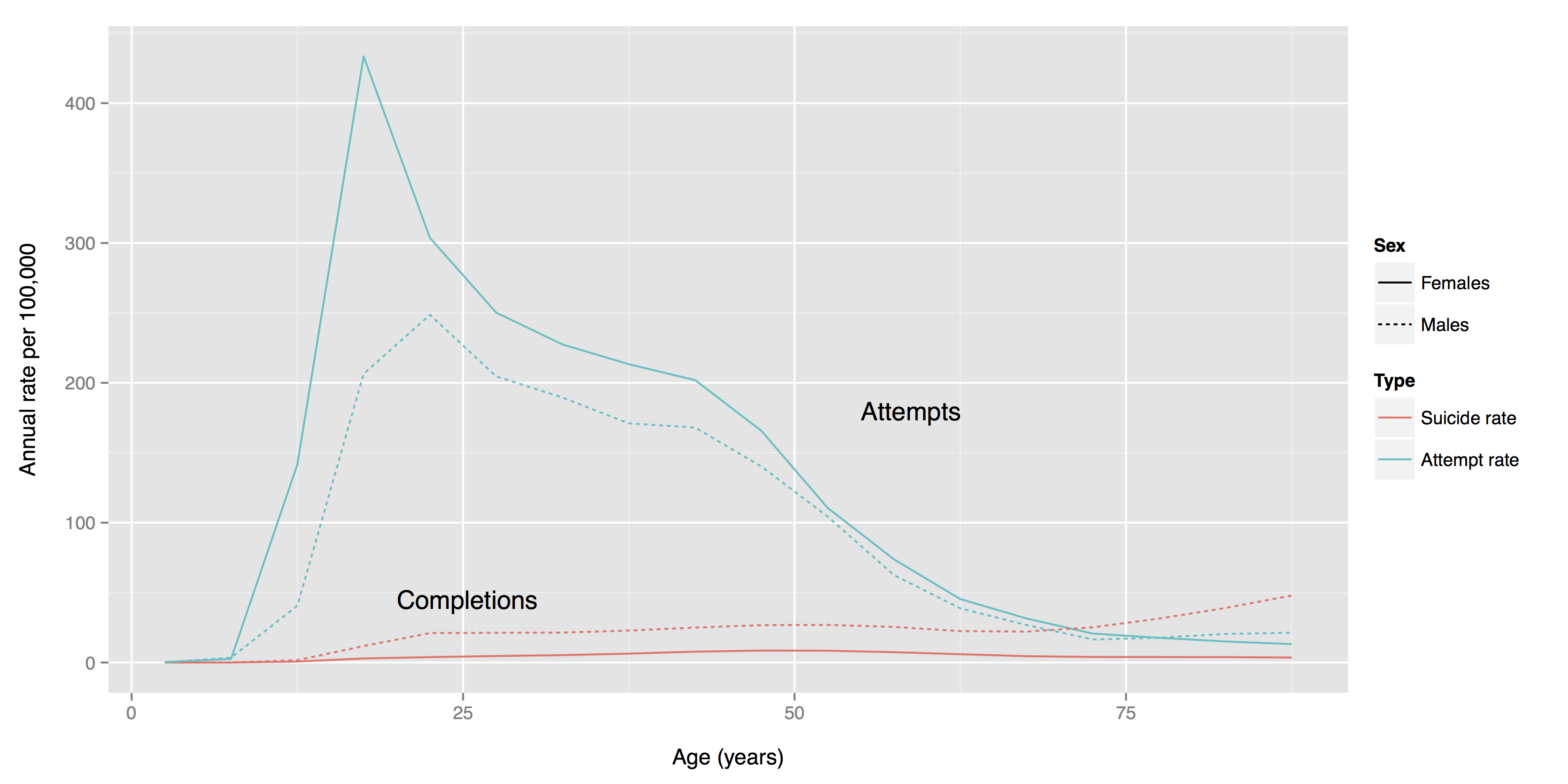

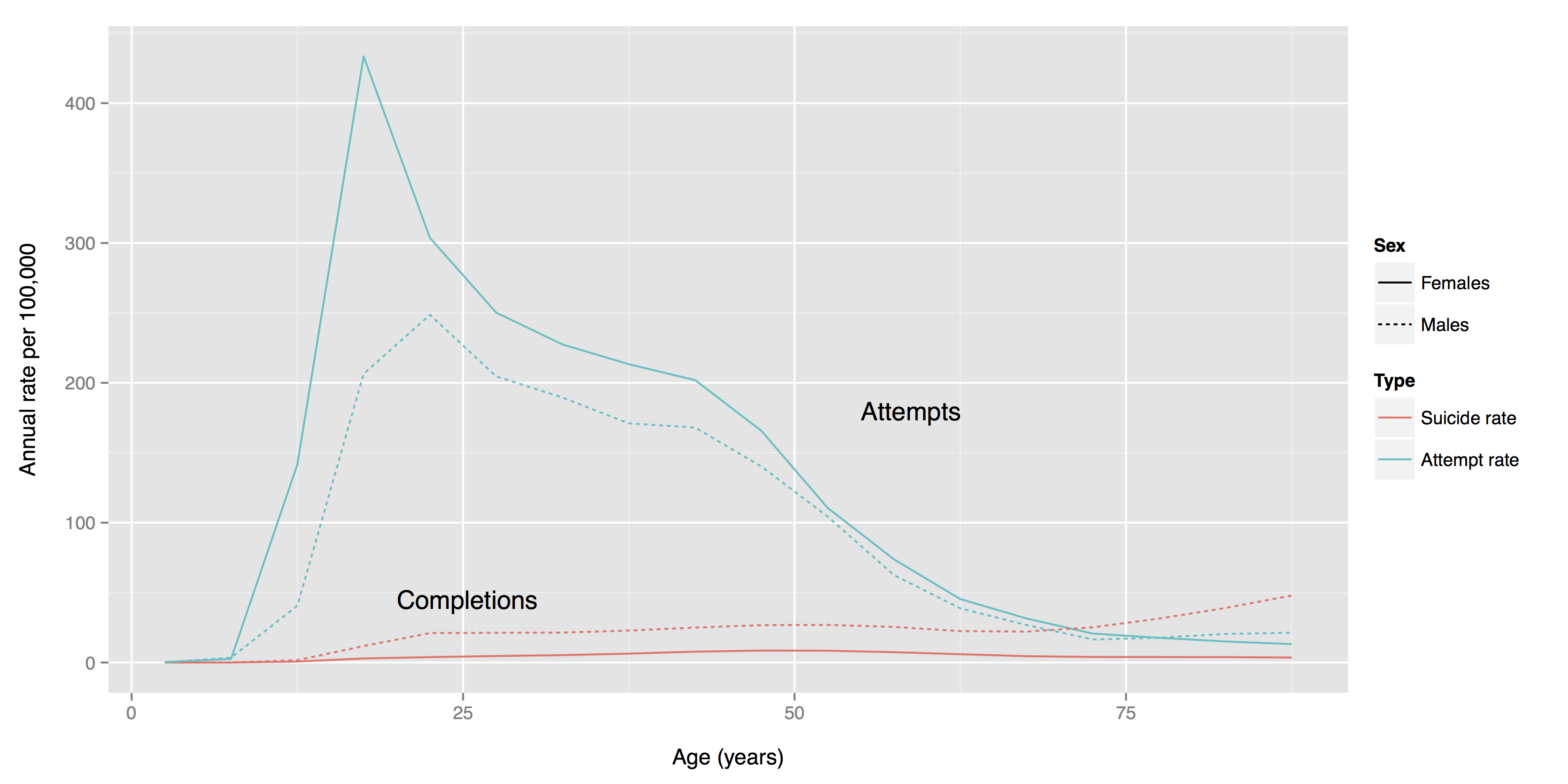

Our hypothesis requires that attempts are much more common than completions. The costly signal only succeeds if the victim survives her attempt and her social partners consequently make changes that benefit her. Attempts are indeed vastly more common than completions, especially among young women:

Our theory is far from proved. You can read more about it and supporting evidence in this paper and in an earlier paper on self harm. But, despite over half a century of research, the mainstream view that suicidality is a type of psychopathology, that victims’ brains are dysfunctioning and must be fixed with drugs or therapy, has also not come close to being proved.

If we are correct, there is nothing wrong with the victim. Instead, there is a profound problem in her social environment. The most effective response to her suicidal behavior would be to substantially improve her life.

In particular, victims of physical or sexual assault — perhaps the strongest risk factors for suicidal behavior — need those closest to them to believe them and protect them. Therapy can be enormously helpful, not because it fixes a broken brain, but because it provides exactly the understanding and support that victims desperately need.

It is time to ask: does the mainstream model of suicide, by focusing on the putative psychopathology of the victim, help silence her cry for help?